Ñuka ñawita tapani

Cierro mis ojos

I close my eyes

Panga Tukuni

Me transformo en hoja

I transform myself in a leaf

Waira urmachiguan

El viento me hace caer

The wind makes me fall

Allpa shunguluan ullariguan

La tierra me abraza con su corazón

The Earth hugs me with her heart.

-Poem by Mukutsawa Montahuano.

NAKU means forest.

To be Sapara means to be a woman or a man from the jungle, the caretaker of the jungle. Naku, 'the forest,' is not only a physical place but a living world constituted by many spirit beings, human and non-human. These spirits communicate through a semiotic process wherein other than human beings, such as animals, landforms, rivers, rocks, and trees, carry out thoughts and agency.

The Sapara worldview is shaped by the health of the land and their daily interactions with the various spirits of the jungle through dreams. The place is endowed with significance. A destroyed land results in the loss of access to dreamtime, jeopardizing the Sapara's cultural identity.

PAJU means power in the hands to heal or perform a specific activity

Pajus are knowledge or powers the Sapara possess. This includes understanding the healing properties of plants, rituals, handmade ceramics, harvesting, hunting, fishing, and foraging; as well as planting, cultivating, collecting, and preparing medicines for cleansing or healing. Pajus are transmitted from one generation to the next, embodying the concept of Unantsay, which means that present-day Sapara live by the teachings of their grandparents. Similarly, these grandparents followed the wisdom of their ancestors, continuing a lineage of knowledge.

KUSMUY means dreams

For Sapara people, dreaming is considered a privileged entrance to ancestral knowledge. To dream is to understand a language of symbols where representations are intuitive and guided by their interpretative process of the self, body, and spirit through corporeal and oneiric experiences.

“My Sapara name is Suyauna, which means big tree. I am a tree that keeps growing, I attract many birds and give strength to the Earth.”

In Between Dreams the Forest Echos the Song of the Burning Anaconda

2021 - ongoing

Ancestral Sapara teachings of witsa ikichanu, “good living,” mean safeguarding the energy of the river, the forest, and the wind through a harmonious connection to the land and a receptive bond to the spirit world through dreams. In the same way that stories reveal themselves in our physical realm, dreams tap into memories to weave a collective essence that resonates within the body.

Indigenous Sapara people’s struggles have roots in the extensive attempts of the illegal extraction of fossil fuels in their territory. Having previously assumed the extinction of the Sapara due to the effects of colonialism, the rubber trade, migration, diseases, and enslavement. In 2001, UNESCO recognized the Sapara Nation from the Ecuadorian and Peruvian Amazon as an “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.” Today, fewer than 600 Sapara remain, and only three elders speak their native language.

In Between Dreams the Forest Echos the Song of the Burning Anaconda is a long-term visual and research project in collaboration with Indigenous Sapara women from the Ecuadorian Amazon. The project delves into themes of dreams, gender, body-territory relations, identity and belonging, and environmental conservation through multidisciplinary storytelling of Sapara women’s pursuits of ecological well-being and the local concepts of place-based perspectives to highlight the idea that the body is also considered a place of resistance, principally because of how extractivism is rooted in the colonial dynamic of oppression over women and nature.

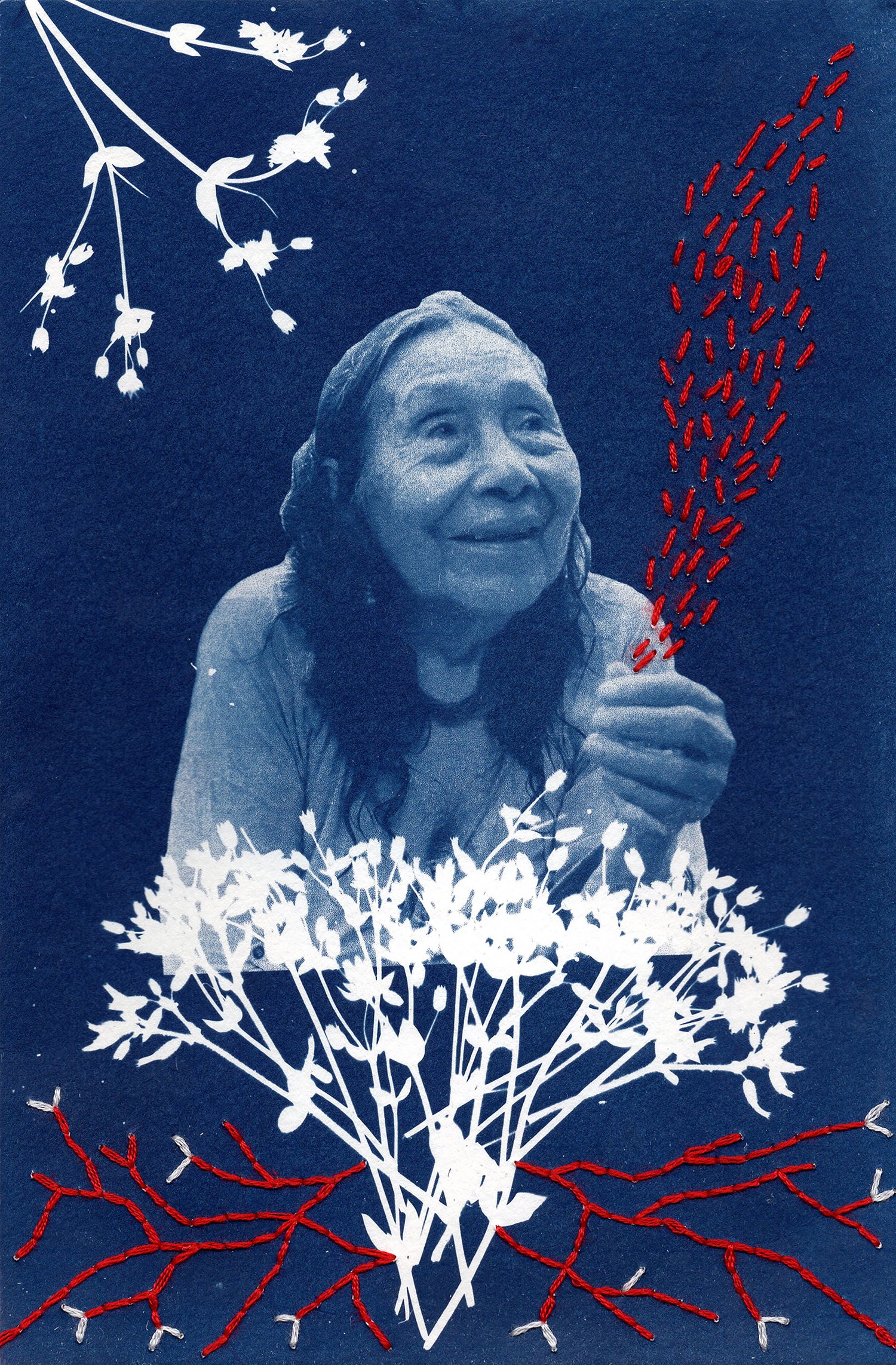

Through documentary photography, video, and embroidered polaroids and cyanotypes, this work explores notions of trans-corporeality and intersectionality to weave stories of the intimate and symbolic relationship Sapara women share with the land, the other than human kin and how dreams re-frame their sense of belonging and ancestral knowledge. The cyanotypes pose a reflection of connectedness and destruction. Symbolically, the blue color represents the bodily waters, and the red string highlights the ancestral lineage. It is said that when we stop to think about how individual bodies become implicated with other bodies of water, we start moving beyond objectification and towards new imaginaries of living and engaging the land. The Polaroid images serve as heirlooms. By embroidering these polaroids, Sapara women become their own storytellers, resignifying their memories and oneiric experiences from a place of autonomy while honoring their spiritual connections that recognize human identity is not outside of nature but rather within it. Photo embroidery becomes a mending ritual. It is a way to untie or dismantle the norms of oppression by reconstructing new narratives. Each stitch is seen as a metaphor for liberation.

© 2025 Tatiana Lopez. All rights reserved.Prints and image licensing available upon request.